Scientist Birutė Galdikas inspired by four decades spent in the jungle

Primatologist, conservationist, and ethologist Birutė Galdikas shared her story Monday night about the wild yet gentle orangutan and her life-long mission to protect the endangered primates and their habitat.

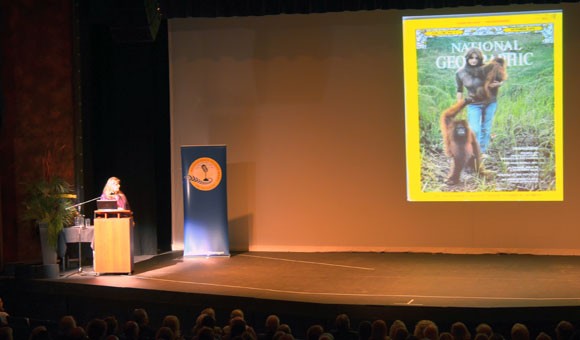

Her talk, Curious Orange — Preserving Orangutans and Forest, was the final event in this season’s Distinguished Speaker Series, presented by UBC’s Irving K. Barber School of Arts and Sciences.

“Orangutans are not our closest relative in the animal kingdom, but they share 97 per cent of our DNA,” said Galdikas. “And the interesting thing about this DNA is that it has not much changed since the ancestors of the great apes and the ancestors of humankind parted ways. So when we look at the orangutan we are looking at a creature that basically has the same, more or less, DNA as the ancestral great ape that was once a sibling of our own ancestor.”

Galdikas has been in Central Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo), studying and protecting wild orangutans and the forest since 1971. She is an expert in wild orangutan behaviour, and focuses her efforts on the development of orangutan conservation programs, and the re-introduction of captured apes into the wild.

“Extinction happens in front of our eyes and we don’t actually see it. We watch it eyes wide open and don’t actually understand it. This is the situation facing all the great apes of today,” she said.

The main threats facing orangutans are poaching, illegal logging, illegal mining, fires, and palm oil plantations.

“Certain biological attributes increase vulnerability to extinction. Orangutan natural history suggests they are susceptible to sudden changes in the environment, and certainly global warming and deforestation are two very real changes to their environment,” said Galdikas. “That said, if orangutans do go extinct in this century, and it might happen, it will be due to palm oil. The one thing that people can do to help the orangutan — and it doesn’t cost a thing — is to stop using palm oil, in all its forms.”

Galdikas established Orangutan Foundation International (OFI) in 1986, which is a non-profit organization dedicated to the conservation of orangutan and their habitat. OFI operates Camp Leakey, an orangutan research centre within Tanjung Putting National Park, and also runs the Orangutan Care Centre and Quarantine facility in the Dayak village of Pasir Panjang, which is home to 330 displaced orangutans, many of which were captured by poachers. OFI helps manage the Lamandau Wildlife Reserve, where rehabilitated orangutans were released into the jungle.

“The orangutan is very dear,” said Galdikas. “When you look into the eyes of these creatures, you are looking into eyes that resemble human eyes; the eyes that gaze back at you reflect your own.”

Primatologist Birutė Galdikas with a 1971 National Geographic cover where she was featured in a story about her work with orangutans in Borneo. Galdikas gave a community talk at the Kelowna Community Theatre Monday night as part of UBC’s Distinguished Speaker Series.

Primatologist Birutė Galdikas talks with audience members following her UBC Distinguished Speaker Series talk, Curious Orange — Preserving Orangutans and Forest, at the Kelowna Community Theatre Monday night.

-30-